When you peruse the headstones of St. Mary’s Cemetery, you find numerous Slavic-sounding names like Kozlova, Holovich, Marusin, and Fecenko. But there in the middle amid Fek, Homsey, and Semansin you will find one John Miller. A decidedly English-sounding name in a decidedly Slavic burial ground. Who was this English-sounding man?

First, to be clear, John Miller was not an Englishman.

In my younger days, the story passed down to me was that John Miller was indeed from the Old Country. He was a Jewish man, an immigrant with no family and without a nearby synagogue. But he was still a part of the community and when he eventually died, the Orthodox community allowed him to be buried among the community. That story and that name always stuck with me.

In my later years I’ve learned that stories are often—though not always—formed around a kernel of truth and that they then branch out in surprising directions with embellishments, fictions, and omissions. So what about the story I was told about John Miller?

Immigrant Among Immigrants

John Miller was not an Englishman in Ganister. The US Census records John living in Ganister from 1900 through 1930, the last in which he would appear. The census takers—at that time you were interviewed by someone on behalf of the Census rather than self-completing the form—consistently captured his name as John Miller, unlike the variations we see for many of Ganister’s immigrant families and their descendants. Furthermore, the four censuses where we find John, 3/4 place his arrival in 1889 and the outlier is only off by two years, 1891.

The same censuses also point to a similar background as those of the Slavic community. Europe’s political geography changed significantly from the 1870s through the 1930s—let alone afterwards—and John’s life captures that history. In 1900 he was born in Austrian to Austrian parents.1 In 1910 John is now born in “Austria-Slavonian”, which isn’t a place but almost certainly meant Austria–Hungary.2 Then in 1920, after the First World War, the census lists John and his parents as being from Czecho-Slovakia, which came into existence after the war.3 But then in John’s last appearance in the 1930 census, he was born in Hungary as were his parents.4

We can conclude that John was most likely born into and originated from one of the Slavic communities that dominated Ganister, those that lived in or near the Carpathian Mountains. Those that stayed in the Old Country saw that area change from Austria to Austria–Hungary to Czechoslovkia, Poland, or the Soviet Union and then some back to Hungary and then back to Czechoslovakia, Poland, but also the Soviet Union, those in the Soviet Union saw Ukraine replace that identity. And then in 1993 Czechoslovakia split and that part of the area became Slovakia.

So where in all that craziness was John Miller born? Unfortunately I don’t know. Tracing his immigration has proved elusive, because John Miller was almost certainly not his birth name. And it turns out there were more than a few John Millers arriving from the British Empire and John Miller isn’t terribly far removed from Johan Muller and the spelling variations thereof from Germany.

A Quarryman’s Life

John eventually settled in Ganister by 1900 where he worked as a quarryman. I don’t know where he worked before then, though it’s distinctly possible he headed straight for Ganister, in 1889 the Pittsburgh Limestone Corporation, which operated the quarries that became the Blue Hole, had yet to lease the land for its operations. I’m not aware of when the Saint Clair quarries opened and so he possibly could have started there.

Regardless, by 25 June 1900, John lived as a single, 30-year-old boarder in Ganister, residing with Joseph Conrad and his family. Two other boarders lived in the household: another Conrad, Nicholas, and Peter Woshish. Except for Joseph’s children who were all born in Pennsylvania, the whole household were natives of Austria. And again except for the children, and in this Joseph’s wife, they all worked in the quarry.

Not long after that 1900 census recorded John as single, he must have met a woman named Annie. Because according to the 1910 census, the two married in 1901, though to date I haven’t had an opportunity to research their marriage certificate. Consequently I know little about her, though she was 11 years younger and had arrived in the United States only in 1900. Like John, she and her parents were born in Austria–Hungary.

The couple does not appear to have had any children, at least not in their first nearly decade of marriage, because in 1910, the census recorded John and Annie living in Ganister with zeros for the columns of living children and total children. They did, however, have a boarder residing with them, John Sqivil (likely Skvir). The couple’s home was almost certainly small and John rented it rather than owned it outright, as was the case for many of the quarrymen.

By 1910, the census also noted that John could speak English. He could neither read nor write, but he had learned to communicate in English. Contrast that to his wife Annie, who could not speak English, but was able to read and write in her own language. The census also recorded information about John’s citizenship. Despite arriving in the United States over twenty years earlier, the government still classified him as a legal alien. In fact there I have yet to find any records that John ever applied for American citizenship. Certainly some immigrants did choose to become American citizens, but many others, like John, chose to remain citizens of the Old Country.

In the following decade, John’s circumstances changed. Unfortunately we do not have all the details as the 1920 census recorded only the result. John, who had hosted John Skvir as a boarder now lived as John’s neighbour. And John Miller still worked in the quarry as a labourer. However, Annie Miller was no longer in the picture. The census recorded John Miller, now aged 50, as divorced. That may not entirely be the case, as we shall see shortly, but clearly John and Annie were no longer together. John didn’t live alone, however, as he did host one boarder, Demeter Burjkre.

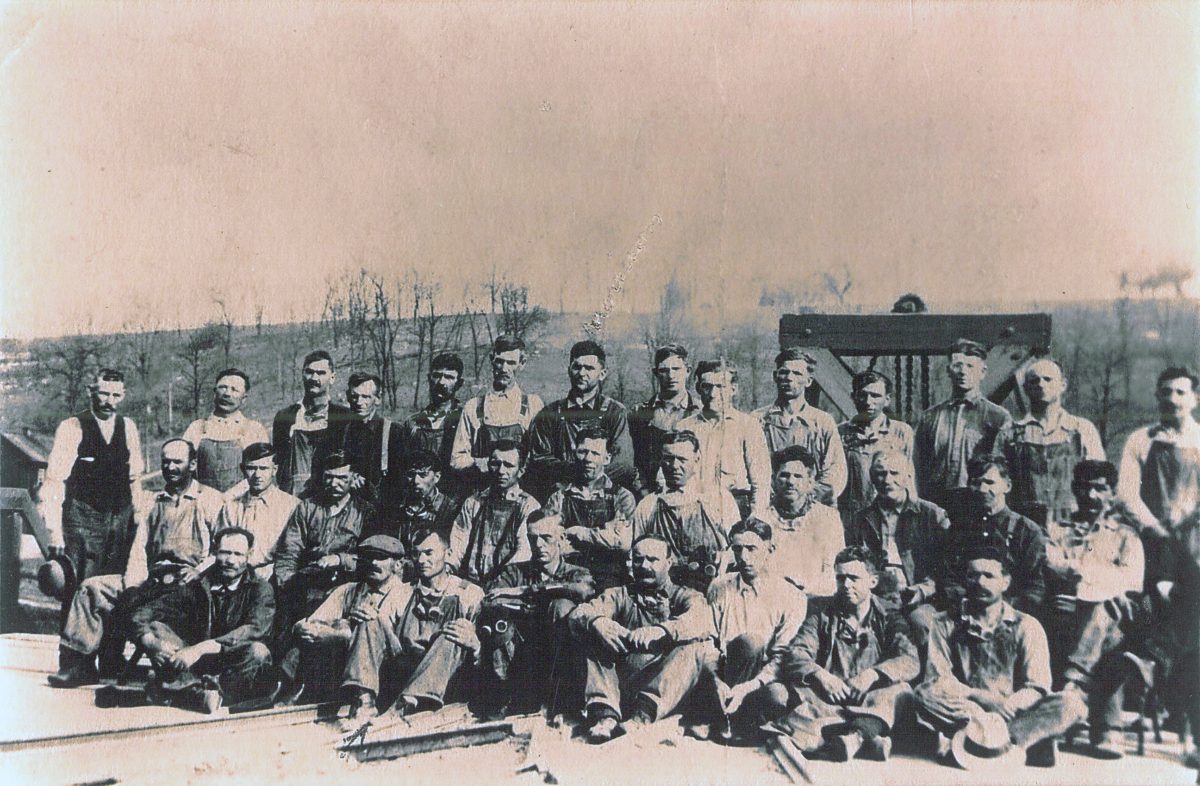

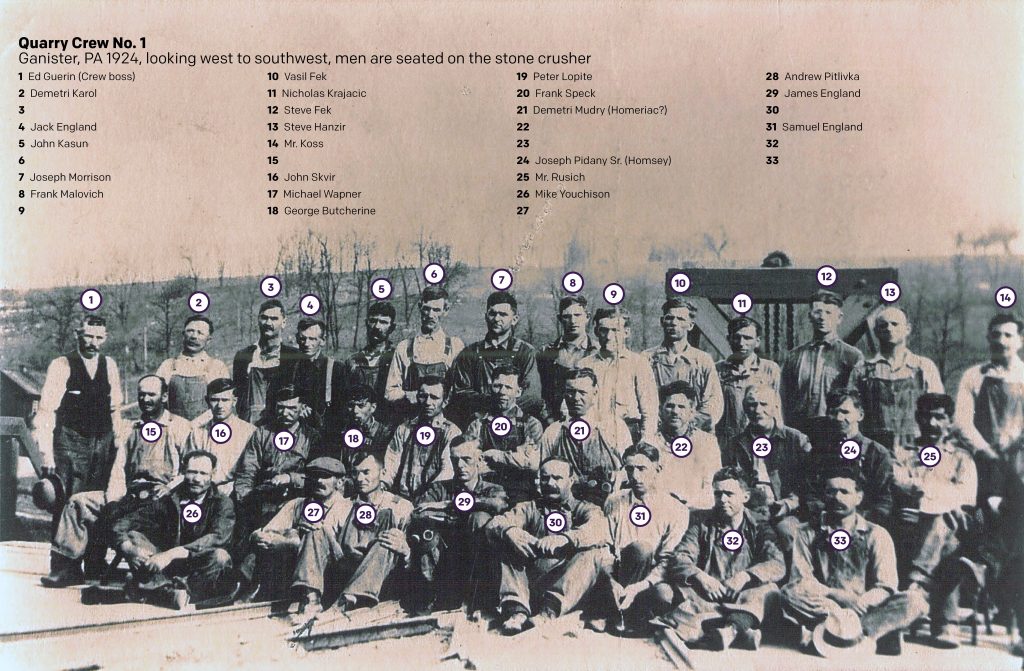

As with the previous decade we know little about the intervening years. During the 1920s, however, he appeared in a photograph of the members of Ganister’s Russian Orthodox church. His entry lists only one notable event that we will address shortly. However, the fact he was a member of the church would seem to disprove the notion that John was a Jewish immigrant.

The 1930 census was conducted in April for Ganister. The occupation listings were more limited than in previous decades as John and his peers were all simply listed together as quarrymen. But given the little advancement he saw in the previous decades, it’s likely John remained a labourer at the quarries. The census does shed a little more light on his background, listing his native language as Little Russian, the same as his Carpatho–Rusyn community members. However, despite being able to speak English, John had still not learned to read or write it.

He now lived as a boarder again, this time in the household of John Fecenko. The house had a value of $1600, very much above the average for the quarrymen community. Presumably it was a larger house with more rooms and it had at least two stories. And while John Miller lived with the Fecenko family, he was still single. Curiously, the 1930 census recorded him as widower, not divorced.

Unfortunately, four months later, surely one of the more tragic moments of John’s life occurred.

John was now a 61-year old man, perhaps divorced, maybe widowed, regardless he was without close family. We know little else about his life or how he felt. But, on Sunday, 17 August 1930, John, presumably still living at the Fecenko home, went to a second-story window and cut his throat with a knife. He then threw himself to the ground, a distance of about 20 feet, but neither attempt killed him. Surely bleeding profusely and injured, John then managed the short distance to Ganister’s bridge across the Juniata River. There he threw himself again to the ground below—not the river—and this time broke his leg. A railroad worker found him lying there and brought him to a physician and from there he went to hospital in Hollidaysburg.5

The church photograph from the 1920s was later detailed by church members and John Miller received a single line: hung himself off Ganister bridge. Of course it’s possible that John on a second occasion attempted to hang himself off the bridge, but contemporary accounts only point to the single instance. His story is clearly more detailed than that—not to mention the incorrect implication of death by suicide—though neither the newspaper account nor the community memory provides any insight to why John resorted to attempting suicide.

That episode of John’s life also is the second to last for which we have either any documentation or anecdote. The last was John’s actual death.

Death

Despite his three (known) attempts to end his own life, ultimately John died of natural causes. Starting at some point in early 1937, he began to suffer from chronic myocarditis. On 1 July he started seeing Dr. Roy Gosborn of Hollidaysburg. However, John eventually died from the chronic myocarditis on 27 July 1938.6

His obituary in the Altoona Tribune was brief. It noted that John had been a widower rather than being divorced. More importantly, the obituary declared he had no known relatives.7

Intriguingly, his death certificate lists his burial place as the Catholic cemetery in Williamsburg. Of course, we know from his headstone he was eventually interred at the Russian Orthodox cemetery. But compared with some of his contemporaries’ headstones that offer some biographic information, John’s is simple and unadorned.

Conclusion

So who was John Miller?

We can be confident that his birthname was Anglicised to the English-sounding John Miller. And that was the name by which he was known in the United States. Was he a Jewish immigrant from the Old Country? Probably not, since he worshipped at the Russian Orthodox church. The families with whom he lived with in Ganister were Carpatho–Rusyns from an area near present Roztoky, Slovakia. John likely hailed from that area or had some kind of connection there. But an examination of nearby villages in the region’s 1869 census hasn’t revealed a Miller family or a family surname that could be easily changed to Miller. Consequently we cannot rule out the possibility that upon arriving in Ganister, he made friends with that cluster of individuals and became part of that community. Indeed, that would broadly fit with the story I was told. He wasn’t necessarily Jewish, but if he was not from the same cluster of villages in then-Hungary, he clearly became part of their Ganister community. They then welcomed John to their church and was ultimately buried in their cemetery. This doesn’t mean that John was not originally a Jewish immigrant—maybe he converted—but there is no evidence yet to support that claim.

Did he truly have no family? That part appears more true and verifiable.

Unfortunately, without any descendants to pass on his story and few written records, John’s life can best be captured as a sketch of quick outlines with little texture available to flesh out his fuller portrait.

Citations

- Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004. Year: 1900; Census Place: Woodbury, Blair, Pennsylvania; Page: 14; Enumeration District: 0097; FHL microfilm: 1241382.

- Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Year: 1910; Census Place: Woodbury, Blair, Pennsylvania; Roll: T624_1318; Page: 17A; Enumeration District: 0091; FHL microfilm: 1375331.

- Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. Year: 1920; Census Place: Woodbury, Blair, Pennsylvania; Roll: T625_1540; Page: 9A; Enumeration District: 127.

- Ancestry.com. 1930 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2002. Year: 1930; Census Place: Woodbury, Blair, Pennsylvania; Page: 4A; Enumeration District: 0083; FHL microfilm: 2341740.

- “Aged Man Makes 3 Vain Attempts to End Life”; Altoona Tribune; Altoona, PA; 18 Aug 1930, pg. 1. Accessed via Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/55413189/

- John Miller Death Certificate. Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Harrisburg, PA; Pennsylvania (State). Death Certificates, 1906-1968; Certificate Number 61444. Accessed via Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/5164/images/42342_2421406260_0672-00526

- “John Miller”; Altoona Tribune; Altoona, PA; 29 Jul 1938, pg. 14. Accessed via Newspapers.com. https://www.newspapers.com/image/57200276/